I’m not a SaaS owner.

Or a product manager.

You could call me a growth hacker (although I don’t work directly at any particular SaaS company).

If pressed for answer, I would consider myself a mere observer. I’m someone who, by staying outside of the typical SaaS structures is able to see things as they really are.

My opinions are free from the pressure of having to reach, communicate with and convince the target audience to buy before my funds run out, for instance.

Or having to manage the growing customer acquisition cost before it outgrows money the app generates.

This allows me to look at things from a different perspective, in detachment from the typical day-to-day struggle of a typical SaaS CEO.

And recently I have been thinking a lot about one issue very close to any SaaS owner’s heart – the product / market fit.

In my research I may have uncovered some intriguing facts.

Because, you see, it may be that the product market fit actually doesn’t exist. At least not in a way we come to define it.

What most startups believe to be the product / market fit.

The term product / market fit is typically attributed to Marc Anderssen, who said that:

“Product/market fit means being in a good market with a product that can satisfy that market.”

According to Carlos Eduardo Espinal,

Product / Market fit can be loosely defined as the point in time when your product has evolved to the point that a market segment finds it attractive so that you can grow your product / company scalably.

In “The Four Steps to Epiphany”, Steve Blank says:

“Customer Validation proves that you have found a set of customers and a market who react positively to the product: By relieving those customers of some of their money.”

According to Sean Ellis, the best way to determine a product / market fit is to use the 40% rule. He writes:

“If you find that over 40% of your users are saying that they would be “very disappointed” without your product, there is a great chance you can build sustainable, scalable customer acquisition growth on this “must have” product.” (source)

In a post on his blog called, “The Pmarca guide to startups part 4: the only thing that matters” (note that the post is now offline. The link goes to the Wayback Machine archived version of the page), Anderssen writes:

The only thing that matters is getting to product/market fit.

He then adds:

“Carried a step further, I believe that the life of any startup can be divided into two parts: before product/market fit (call this “BPMF”) and after product/market fit (“APMF”).”

In the BPMF stage you should do whatever you can to achieve the product / market fit:

Change out people, rewrite your product, switch to a different market, tell customers no when you don’t want to, tell customers yes when you don’t want to, raise that fourth round of highly dilutive venture capital, whatever is required.

But, does a product / market fit really exist?

Recently I came across an older post on the Anderssens blog written actually by Ben Horowitz in which he discussed potential myths with the PMF. Myths that in my opinion might be rendering it useless. Here they are:

Myth #1: According to Horowitz finding PMF is never a distinct event you simply can’t miss.

As he writes:

“Some companies achieve primary product market fit in one big bang. Most don’t, instead getting there through partial fits, a few false alarms, and a big dollop of perseverance.”

In fact, as Horowitz points out that a company could easily find several smaller PMFs in smaller markets it might have never targeted. Or find a smaller PMF while searching for that big one they originally set themselves off to find.

Myth #2: Turns out you might also completely miss the fact of actually achieving a PMF.

PMF is more complex that it might seem. And thus, it could be hard to define what metrics could actually prove that you have it. Could it be the number of customers? Site traffic? Monthly recurring revenue?

Myth #3: Even if you’ve found a PMF, it’s not a given that you’re going to keep it forever.

To most companies, PMF is a sweet spot that once reached will guarantee their success for years to come. After all, they have the market that loves the product and all they should focus on now is growth.

But then, companies that achieved a PMF (measured by Sean Ellis’ 40% rule or simply, by recurring monthly contracts they’ve generated) might suddenly face some tough times.

The market might change. And your solution might no longer be relevant to the audience.

Or a new development decision might steer your product away from the original PMF.

Myth #4: Once you win the PMF you can stop worrying about the competition

It seems that to many startups, reaching a PMF is a signal of absolute victory. Suddenly the competition becomes irrelevant. In their eyes, they own the market and so, they’ve won.

But all it takes is a new entrant to the market to disrupt it and throw you off your PMF. Just look at the havoc the arrival of Airbnb caused in the hotel industry.

So is there even any way to guess if you have reached the PMF?

There’s actually a number of ways you could use to find out:

First, you could use Sean Ellis’ Survey.io app and follow his 40% rule we talked about earlier.

Or use the monthly recurring revenue as a guiding factor. Here’s a great explanation how it works by Brad Feld.

Or define any other metrics to measure your SaaS’ success.

The Most Important SaaS Metrics

As I wrote earlier, a challenge with defining PMF is that it’s hard to pick that one metric that could reveal it. Instead, you might have to try a few. Here are the most important ones to choose from:

Monthly Recurring Revenue (MRR)

SaaS is all about building a sustainable business.

But let’s be honest, the road to it is far from easy.

For one, you have to survive long enough before the money you collect from monthly subscriptions offset the investment and begin to cover your daily business expenses.

And MRR is a metric that helps you establish how your income stacks up on regular basis.

MRR tries to predict the revenue you expect to receive each month.

The easiest way to calculate it is to multiply the total number of paying customers by the average monthly revenue per customer.

So, 10 customers paying you $79 per month on average would equal to $790MRR.

Of course this is the simplest way to do it. You could go much deeper. But if you want a quick answer what’s your MRR, that’s the best way to go about it.

Customer Churn

SaaS business model relies on retaining customers for longer. The goal of SaaS marketing for instance isn’t just to attract the right people but also to retain them for as long as possible.

But there will always be people cancelling their subscriptions. And churn is a metric that measures their number each month.

A high churn rate signals that there’s something wrong with your SaaS product. If that’s the case with your product, noticing a higher churn should mean that you drop everything you do with marketing and begin fixing that problem.

Cost Per Acquisition (CPA)

The cost of acquiring customers is often the largest expense for SaaS companies.

Having a high CPA may suggest you’re not using the most effective marketing channels. Or that your journey to purchase is too complex for customers.

To avoid this, you need to track cost per customer acquisition – how much it costs you to acquire each paid customer to your business.

Calculating this metric is actually quite simple. Add up all your monthly marketing and sales expenses. Then divide that number by the number of new customers you acquired in the same period. You’ll end up with the average amount you spend to acquire a customer.

Average Revenue per Customer

This metric is actually pretty straightforward. It tracks the average revenue you’ve already received per customer.

Lifetime customer value

This metric on the other hand helps to establish what revenue you could expect from your customers in the future.

The simplest way to calculate it is by combining the average revenue per customer and the churn rate. But you could go even further and add the cost per acquisition or cost of providing customer service.

Product Usage

I know, on the outset, the data on how your users use the product doesn’t seem relevant.

But…

What if half of your users don’t login to the app regularly? Or fail to use the most crucial feature of the app?

Perhaps they’re not finding your app useful. Or it’s too confusing for them to use. Such behavior could only lead to a higher churn rate.

So at most I believe that you should track such customer actions as:

- Frequency of logins to the app,

- Session length,

- Most common functionality they use (and what they haven’t even set up), and

- Gaps between each sessions.

Combined with your knowledge of the app you should be quickly able to discern any negative patterns and then come with a plan to turn them around.

Cash

In business, cash is king. You could have the best product in the world and plenty of users. But the moment you run out of cash, you’re done.

So keep track of the money you have in your bank account. Hat you’re looking for is not only the total number. You need to ensure that you have a viable cash-flow (more money coming in than coming out).

Lean Analytics

The last thing I want to highlight today is a concept originally described by Alastair Croll and Ben Yoskovitz called Lean Analytics.

If you aren’t sure what’s Lean Analytics, let me go over that very quickly.

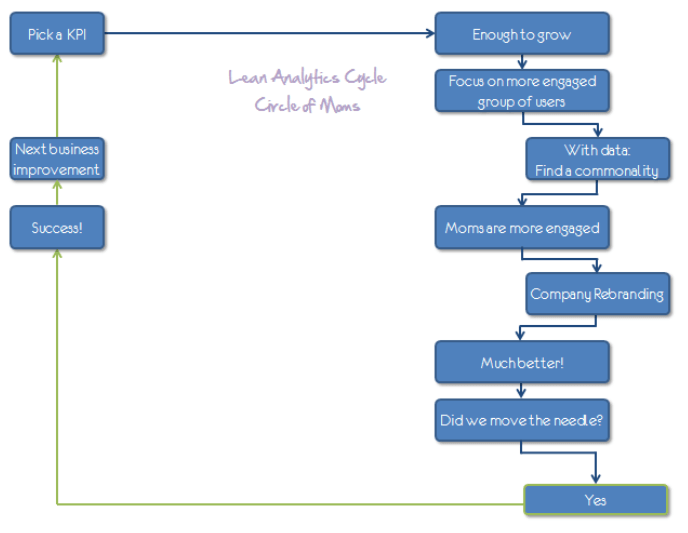

Lean Analytics (or LA Cycle, to be precise) is a system that helps to, in a sustainable way, drive change in the business.

The Lean Analytics Cycle is a simple, four-step process that could easily be summed up as (in the words of Alastair Croll):

“First, you figure out what you want to improve; then you create an experiment; then you run the experiment; then you measure the results and decide what to do.”

Here’s a great presentation by Hiten Shah outlining the whole process:

And here are some really amazing case studies how using Lean Analytics has worked for companies like AirBnB or Circle of Friends.

Is Lean Analytics the best way to achieve a PMF?

In my opinion, yes.

It’s the only process I can think of that takes incremental change into consideration.

The thing to remember about PMF is that your search for it is continuous and never ending. Even if you think you have it, or the numbers say you do there might still be another PMF to find. And you can get to it only by a continuous and incremental change.

And of course, once you get there, you need to keep iterating because, you know:

PMF doesn’t last forever.